Arrested but undaunted, a young artist challenges an ageing autocrat

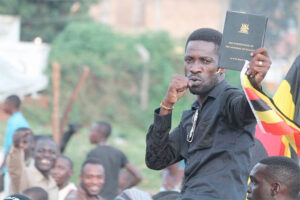

Suit torn, tie askew, eyes half-shut, Bobi Wine stood on his veranda and addressed a crowd. That morning, on November 3rd, the Ugandan pop star had handed in his nomination papers to run for president in elections in January. Moments later, police smashed the window of his car, arrested him and pepper-sprayed his face before driving him home. Bedraggled but defiant, he greeted his fans. “This is a revolutionary election,” he said. “If it’s a boxing fight, it has begun.”

Ugandan elections are only loosely about votes. Yoweri Museveni, the president, has ruled since fighting his way to power in 1986. He needs a contest to legitimise his regime, and uses the army, police and patronage to make sure he wins. The opposition hopes to unseat him by opening cracks in his regime. Mr Bobi Wine’s struggle is part election campaign, part call to revolution. “Running against Museveni”, he tells FremerMedia , “is like running against all the institutions of state.”

For Mr Bobi Wine, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi, it has been a meteoric rise. He found fame as the “ghetto president”, singing about social injustice. In 2017 he won a seat in parliament. Mr Museveni’s acolytes were busy abolishing a presidential age limit so the old man could stand again; Mr Bobi Wine joined opposition mps in resisting the change. The bill passed, but Mr Wine channelled the energy of the campaign into a new movement, which he called “People Power”—a messy coalition of established politicians, frustrated graduates and the hustlers of his ghetto hinterland.

Bobi wine hold a meeting with ugandans

People Power speaks with many voices. In the flood-prone valleys of Kampala it sounds like a revolt against the rich. On university campuses it resembles a youth rebellion. Activists in the neglected north frame it as a fight against ethnic exclusion. “All those are just symptoms of one issue: misgovernance,” says Mr Wine. At 38, he is half the incumbent’s age.

The movement was also, at its inception, a protest against conventional politics. But in July Mr Wine announced himself the leader of an obscure party, which he renamed the National Unity Platform (nup). A party structure gave him control over candidates, a symbol on the ballot paper and a firmer legal footing. Some considered it a wrong turn. “We are now behaving like politicians,” says Roy Ssemboga, a former student leader, once close to Mr Wine, who is running for parliament as an independent. “We wanted short-term glory and I think we lost an identity.”

Like other parties, the nup has become caught up in Uganda’s transactional politics. The process of selecting parliamentary candidates exposed disorganisation and division. In the central region, where the party is strongest, some contenders tried to buy its endorsement. Derrick Ssonko, a mechanic, says he was inspired to run for local councillor, but the party ticket went to a rival who paid a bribe. He worries that the nup is “old wine in new bottles”, even though everyone he knows will vote for it.

Lewis Rubongoya

The nup is contesting fewer than half of parliamentary seats. David Lewis Rubongoya, the party’s powerful secretary-general, says that scores of contenders pulled out because of a court case that challenged its legal status (the case was dismissed, but only after nominations had closed). Many others could not muster nomination fees of 3m shillings ($800), which is the average annual income in Uganda.

But the paranoid president is not the type to take chances. He warns that Mr Wine has “foreign backers who fear a strong Uganda”. Soldiers and police raid the nup’s offices on spurious pretexts, and invoke covid-19 to block public gatherings. Activists are threatened or bought off. In 2018 Mr Wine was beaten by soldiers and charged with treason, along with 36 of his supporters (a conviction is unlikely). Voters are wary of the disorder that has always accompanied political transition. After listening to an nup activist in a northern village, 80-year-old Rose Akello raises her hand. “Death is painful,” she says, recalling Uganda’s violent past. “When you are pursued by a knife, don’t you go and hide?”

Kizza Besigye, the main opposition leader in the past four elections, is sitting out this poll, arguing that Mr Museveni cannot be removed by voting alone. Some activists in the nup agree, but also blame Dr Besigye for demoralising voters. Their apparent strategy is to draw a massive turnout, then “defend the vote” on the streets. “A vote must be cast before we can fight for it,” says Mr Wine.

Powerful critics, such as Andrew Mwenda, a journalist who is close to the president, argue that Mr Wine’s supporters are “radical extremists”, not liberal democrats: “They’re fighting Museveni to get power and do exactly what he’s doing, perhaps without his finesse.”

Also read: Sudan’s decision to join Abraham Accords unlocks US and regional aid

Others try to paint the nup as a party of Buganda, an ancient kingdom within Uganda in which Kampala lies. Buganda’s kabaka (king) commands deep loyalty among the sixth of Ugandans who consider themselves his subjects, including the singer. Several leading politicians in the nup cut their teeth on royalist struggles for land and federalism. Buganda has “legitimate and genuine concerns”, says Medard Sseggona, an nup politician and former minister in the kingdom’s own cabinet, but those “are shared by other nationalities in this country”. Mr Wine himself has cosmopolitan instincts, nurtured in the ethnic melting pot of the city.

In general, Mr Wine’s politics are less revolutionary than his lyrics and red beret suggest. His headquarters are painted with murals of pan-African heroes like Thomas Sankara, a socialist leader of Burkina Faso. But he also collaborates with free-market think-tanks. “I don’t have a very radical programme,” he says. His most consistent pledge is to rebuild institutions after decades of personalised rule.

The singer will probably never become president. Even if he dislodged Mr Museveni, any transition would be directed by the army. But the real force is not Mr Wine—it is the hope he represents. From markets to minibuses, Ugandans repeat his slogan, “twebereremu”. What does it mean? His eyes light up. “Get involved.”

Read also : Zari Hassan Endorses Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu aka Bobi Wine

Bobi Wine and Barbie Kyagulanyi